+1 (862) 222-0442 (EST)

Pegasus and the Horses of Ancient Greece

Pegasus and the Horses of Ancient Greece

A history of the mythology and symbolism by Maria Evangelatou

A nod to the most highly regarded animal in the ancient Greek world

Pegasus, the flying horse of Greek mythology, is one of the most admired creatures of the Greco-Roman tradition and a beloved subject among jewelry makers and wearers from antiquity to the present. Usually depicted in flight, Pegasus inspires viewers with his grace and elegance, and carries positive associations of high achievement and success.

To understand the significance of Pegasus in ancient Greek culture, one must first consider the paramount importance of the horse, probably the most frequently depicted and highly regarded animal in the ancient Greek world.

As strong and speedy, clever, faithful and brave companions, horses were essential in ancient Greek warfare but they were also prominent in times of peace, as symbol of wealth and high status for those who could afford to own and maintain them.

One of the most famous riders in Greek history was Alexander the Great (b.356-d.323), here in a modern statue at Thessalonike, Greece. The Macedonian king concurred the Persian Empire on the back of Boukephalas (“Oxhead”), depicted with bull horns on a rare coin of 281 BC.

One of the most famous riders in Greek history was Alexander the Great (b.356-d.323), here in a modern statue at Thessalonike, Greece. The Macedonian king concurred the Persian Empire on the back of Boukephalas (“Oxhead”), depicted with bull horns on a rare coin of 281 BC.

Great generals and warriors rode in battle on horseback, while outside the battlefield, powerful rulers and other wealthy men won recognition by entering their horses in athletic competitions.

The most prestigious was the four-horse chariot race at the Olympic Games, the only Olympic sport in which women could also compete by entering their horses.

Charioteer racing on a four-horse chariot.

Attic Panathenaic amphora, 490–480 BC, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu.

Charioteer racing on a four-horse chariot.

Attic Panathenaic amphora, 490–480 BC, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu.

The horse’s paramount cultural importance in the ancient Greek world is vividly expressed through its prominence in mythology.

Poseidon, the god of the sea and of earthquakes was also the god of horses. Perhaps it is no coincidence that rolling waves are reminiscent of galloping horses, and when a herd of horses run together on dry land, the earth seems to shake.

Poseidon (Roman Neptune) and his horses, painting by Walter Crane, 1910..

Poseidon (Roman Neptune) and his horses, painting by Walter Crane, 1910..

Gods and goddesses were often shown driving chariots with wonderful, immortal horse who were said to be children of the four winds (an apt reference to the animals’ speed).

The divinities Helios and Selene (Sun and Moon) flew across heavens in such chariots, at times depicted drawn by winged steeds (Pegasoi, plural form of Pegasos).

Helios on his chariot, krater (vessel for the mixing of wine and water), around 430 BC, British Museum, London.

Helios on his chariot, krater (vessel for the mixing of wine and water), around 430 BC, British Museum, London.

The most famous of all flying horses was the “original” Pegasus (Geek Pegasos), born out of the severed neck of Medusa when she was decapitated by the hero Perseus who was assisted in his quest by the goddess Athena.

The name Pegasos might derive from the Greek verb pegazo (to gush forth) and the noun pege (source, fountain).

Pegasus not only gushed forth from his mother’s neck but he was also said to create sources of water when he struck his hoofs on the earth. His father was Poseidon himself, god of horses and salty waters.

Perseus slaying Medusa (with the help of Athena) and the birth of Pegasus, by John Singer Sargent, 1922-25, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA.

Perseus slaying Medusa (with the help of Athena) and the birth of Pegasus, by John Singer Sargent, 1922-25, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA.

In ancient Greek myths, Perseus was the hero who caused the birth of Pegasus but was not usually mentioned as the one who rode him (contrary to the claims of contemporary Hollywood movies) That honor rested with the hero Bellerophon (or Bellerophontes), a Corinthian prince who according to some sources was sired by Poseidon in union with the queen of the city.

Bellerophon was charged with the task of killing the Chimera, a winged and fire-breathing monster with the body of a lion, a snake tail, and a goat’s head growing from its back. If horses carried warriors in battles on dry land, certainly a winged horse was required to defeat a flying opponent! Athena herself either tamed Pegasus or helped Bellerophon capture and master the winged horse while he was drinking water at a Corinthian spring. According to another source, Poseidon himself gave Pegasus to Bellerophon.

Bellerophon kills the Chimera on the back of Pegasus - Floor mosaic from Rhodes, 3rd c. BC, Archeological Museum of Rhodes. Pegasus was often depicted together with Athena on Greek silver coins of Corinth and of other Greek cities that were founded by Corinth (here a 4th-3rd c. BC example from Syracuse in Sicily).

Bellerophon kills the Chimera on the back of Pegasus - Floor mosaic from Rhodes, 3rd c. BC, Archeological Museum of Rhodes. Pegasus was often depicted together with Athena on Greek silver coins of Corinth and of other Greek cities that were founded by Corinth (here a 4th-3rd c. BC example from Syracuse in Sicily).

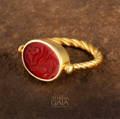

To the left (above) we see a ring depicting Bellerophon that was crafted around 330 BC by "the Santa Eufemia Master" who lived in Tarentum (a Greek colony in the South of Italy). Historians have credited him with many such masterworks by tracing the hallmarks of his style.

After killing the Chimera, Bellerophon rode Pegasus against armies of mortal enemies (the Solymoi and the Amazons) whom he also defeated. Infatuated with his success and with the power he felt on the back of Pegasus, Bellerophon grew insolent and attempted to fly to mount Olympus and live among the gods. His punishment was unavoidable and variously described by diverse sources: either Zeus caused him to fall off of Pegasus, or Bellerophon got dizzy and lost control, or the horse himself threw the rider over and continued his flight to reach the gods. So while Bellerophon got killed from the fall or roamed the earth miserable and alone, Pegasus lived on Olympus and carried thunderbolts for Zeus. Eventually, the flying steed was rewarded for his dedicated service, when Zeus himself placed him on the firmament as the northern constellation of Pegasus.

Pegasus’ symbolism changed over the centuries, serving diverse needs. In the ancient Greek world, he was primarily associated with bravery, success in battle, protection, duty, and commitment. Such meanings made Pegasus very appropriate as a military symbol, so he was chosen as the emblem of at least four Roman Legions.

Pegasus’ symbolism changed over the centuries, serving diverse needs. In the ancient Greek world, he was primarily associated with bravery, success in battle, protection, duty, and commitment. Such meanings made Pegasus very appropriate as a military symbol, so he was chosen as the emblem of at least four Roman Legions.

Ring of a Roman soldier from the Legio secunda Augusta (“Augustus’ second Legion”) established in the 1st c. BC. Pegasus was one of this legion’s emblems.

A Museum reproduction ring featuring Pegasus.

By the 19th century, Pegasus was also considered a symbol of artistic inspiration (the source of creative power). The roots of this concept might go back not only to the etymology of the name of Pegasus and his soaring flight, but also to a brief reference in ancient Greek mythology that placed the flying horse on mount Helicon during a singing competition between the immortal Muses, sources of artistic inspiration, and a group of mortal singers.

During that event, Pegasus is said to have created with his hoof Hippokrene (“Horse-spring”), a source of water that became sacred to the Muses and through its flowing water could also symbolize artistic inspiration.

During that event, Pegasus is said to have created with his hoof Hippokrene (“Horse-spring”), a source of water that became sacred to the Muses and through its flowing water could also symbolize artistic inspiration.

St. Paul Institute of Arts bronze medal, by Paul Manship, 1916. On one side a Muse with lyre and the statue of Nike (Victory), on the other Pegasus with the radiant sun and victor’s wreath. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

St. Paul Institute of Arts bronze medal, by Paul Manship, 1916. On one side a Muse with lyre and the statue of Nike (Victory), on the other Pegasus with the radiant sun and victor’s wreath. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Other equine characters of Greek mythology remind us that Pegasus was one out of many manifestations of the primacy of the horse in Greek culture, art, and imagination. Horses are particularly prominent in the Iliad, the 8th-c. epic poem dedicated to the Trojan War. The greatest of all Trojan heroes, Hector, is called “tamer of horses” (as are many other heroes) and even his wife Andromache is involved in taking care of his animals by giving them grain to eat and wine to drink! The greatest hero of the Greek camp, Achilles, owns two divine horses that draw his chariot and form a strong bond with their master and his closest friend and charioteer, Patroclus. Thus, the horses cry inconsolably when Patroclus is killed in battle. Achilles honors his friend with lavish funerary rites that include a chariot race and the sacrifice of four horses. Considering the high value of horses, that sacrifice is an exceptional sign of honor (and a custom rarely attested in the archeological record).

Other equine characters of Greek mythology remind us that Pegasus was one out of many manifestations of the primacy of the horse in Greek culture, art, and imagination. Horses are particularly prominent in the Iliad, the 8th-c. epic poem dedicated to the Trojan War. The greatest of all Trojan heroes, Hector, is called “tamer of horses” (as are many other heroes) and even his wife Andromache is involved in taking care of his animals by giving them grain to eat and wine to drink! The greatest hero of the Greek camp, Achilles, owns two divine horses that draw his chariot and form a strong bond with their master and his closest friend and charioteer, Patroclus. Thus, the horses cry inconsolably when Patroclus is killed in battle. Achilles honors his friend with lavish funerary rites that include a chariot race and the sacrifice of four horses. Considering the high value of horses, that sacrifice is an exceptional sign of honor (and a custom rarely attested in the archeological record).

The chariot race held during the funerary games for Patroclus, detail from a painting by Antoine Vernet, around 1790, Museo de San Carlos, Mexico City, Mexico.

A very admirable mythical creature that was half man and half horse was Cheiron (Chiron), teacher of great Greek heroes like Achilles and Jason.

He was the divine son of Kronos, who when surprised by his wife Rhea having sex with another goddess, tried to hide his escapade by transforming himself into a horse. Thus, the child of that union was half horse but unlike the uncivilized half-horse mortal Centaurs discussed below, he was immortal, wise, kind, and cultured. Cheiron trained great heroes to ride, hunt, and fight on his back, and he also taught them medicine, music, and poetry.

The important role of Cheiron as educator of heroes is yet another indication of the high regard the Greeks had for the horse as a creature essential for their civilization.

Cheiron teaches Achilles music, wall-painting from Herculaneum, Italy, 1st c. AC.

Cheiron teaches Achilles music, wall-painting from Herculaneum, Italy, 1st c. AC.

While the ancient Greeks admired the intelligence, strength, and bravery of tamed horses, they were also very much aware of the wildness of untamed horses, which in myths was embodied by the unruly behavior of Centaurs: they were half-horse men who lived in the woods and were emblematic of uncivilized life and the inability to control one’s base instincts.

In the myth of the Centauromachy (literally, “Battle with Centaurs”), these horsy men were invited to the wedding of the Greek hero Perithoos, but unused to drinking wine, they got drunk and tried to abduct and rape the women of the feast, including the bride. Their defeat in the hands of Greek men was often depicted in art and could be used to symbolize triumph over any opponent the Greeks considered formidable yet inferior and bound to be overcome.

Centauromachy scene from a Roman sarcophagus, 2nd c. AC.

However, there was an exception to the animality of the Centaurs, and that was Pholos, a kind and hospitable Centaur who knew how to hold his wine.

When Herakles (Roman Hercules) visited Pholos in his cave, the Centaur warned the hero not to open his wine jar, for its aroma could attract the wild Centaurs of the area. Herakles ignored his host and when the other Centaurs arrived craving for wine, Herakles had to fight them off. Although he was successful, Pholos was accidentally injured by one of the hero’s poisonous arrows and died. Thus the wise Pholos fell victim to the impetuous behavior of the great Herakles.

The story suggests that even a wild creature can find its way to civility, while a high-born man can equally lose his way when carried away by desires. This contrast is reminiscent of the myth of Pegasus and Bellerophon, in which the hero is disgraced by his hubris while the winged horse is distinguished through his dutiful and disciplined behavior.

Pholos welcomes Herakles while a deer and Hermes look on. Attic amphora of around 520 BC.

Maria Evangelatou is a Professor of Mediterranean Studies, Department of History of Art and Visual Culture, University of California Santa Cruz.

Our gratitude to Maria for her research and contributions to this page.